3D PRINTING: Three tales of 3D printers prove how diverse this technology can be.

We could print you if we wanted to – in one piece,” Matt Cone of Cameron Advertising Displays (Camad) told me as he described his company’s 3D printing capabilities. Camad came to 3D printing as a large-format printer in search of a way to excite both new clients and existing ones. Titanic Design approached the technology from the perspective of a manufacturer. WhiteClouds started as a media company, but suddenly found themselves with clients looking for 3D-printed models. But no matter the journey, what I really wanted to know was: How will this innovation change the way we think about the business of visual communication?

The folks at Camad (Scarborough, ON, Canada) had been screenprinting for nearly 60 years and large-format digital imaging for nearly 15 when they were approached by Massivit 3D. “When we were being pitched, we probably sat there and scratched the backs of our heads,” said Vice President Dan Deveau, “but once we saw the press, we just knew.”

Cone wasn’t joking when he said they could print me in one piece. The Massivit 1800’s capabilities span up to 57 x 44 x 70 in. “It was a great opportunity to dive into something nobody else was doing,” said Cone. Camad began operating the Massivit in June 2018, but the learning curve was skyscraper steep. From beginning to end, 3D printing is just a different type of journey.

It starts with a sales call, of course, and according to Harky Aulak, account executive, “It’s a completely different sell.” In some cases, you’re calling on new business; in others, you’re having a new conversation with longtime clients. Often, your clients have to pitch the idea to their clients. “What it’s forced my sales guys to do is circle back,” Deveau said. “This is something that has to be nurtured and coddled and miniatures done; there’s a whole new conceptual thing that needs to be understood by all parties.”

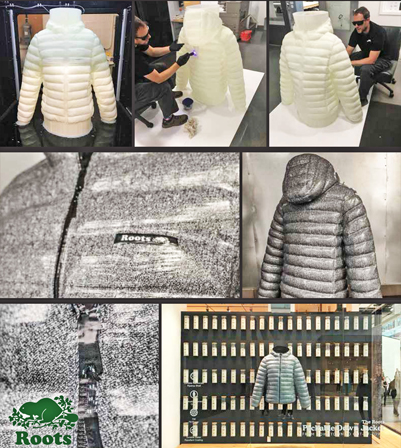

Camad 3D-printed this jacket for Roots, a nature-inspired clothing retailer in Canada.

So what makes all the back and forth, the patience and the intensive customer education worth it? “The wow factor,” said Cone. “Everyone that we presented to said, ‘Wow –could see us doing this,’ or ‘I could see us doing that.’”

The wow factor is just what Roots, a national retailer of nature-inspired clothing, was looking for when they said “yes” to a 3D project with Camad. The ask was simple: a 48 x 26 x 48-in. replica of a jacket. The production was straightforward, as well; Camad scanned the “real” jacket with a 3D scanner to create a 3D file. They printed it on the Massivit and then scanned the original jacket again for color. Camad then printed the solid color onto 3M Controltac IJ180Cv3 vinyl via an EFI VUTEk HS100 Pro and wrapped the 3D-printed model.

The jacket-model hung in Roots’ flagship store in Toronto’s Eaton Centre for a few weeks before Aulak received a call: “We sold out of those jackets. Can you take it down and re-wrap it in another color?”

“Well, absolutely,” Aulak said, so they scanned the jacket again, printed it red, and “up it went.”

“We can’t tell you that it’s the 3D jacket that made them sell out,” Aulak said, “but [they] certainly sold.” Roots has 180 locations around Canada – a new challenge for the Camad team.

ADAPTABLE IS EVERYTHING

In 2019, the word “success” is often synonymous with “adaptable.”White Clouds

(Ogden, UT) is a prime example of adaptability. The business actually originated six years ago as a media company. The plan was to write articles and tutorials about 3D printing. WhiteClouds’ founders had experienced success with other media web properties; 3D printing was the cool new thing, and it seemed like a solid plan.

But before long, folks discovered that WhiteClouds had a few 3D printers behind the scenes – a Maker-Bot Replicator and a 3D Systems Cube – and suddenly engineers and designers were coming to the company for print jobs. “We realized there was more of an opportunity in becoming a print shop versus a media company,” said Cris Fowers, who heads up WhiteClouds’ marketing and business development, and was a part of the company’s founding team.

WhiteClouds settled into a few niche industries: architectural modeling, medical modeling and the world of tradeshows and events. As they produced larger and larger pieces, they realized perhaps 3D printing works best in tandem with other manufacturing processes, and suddenly they had a woodshop complete with laser engravers, CNC machines, foam cutters and more.

The welcome display for this year’s Consumer Electronics Show (CES) was a perfect example of different processes converging. Freeman, the company that manages CES, came to WhiteClouds with 2D artwork and a vision for a welcome display that would capture the spirit of the event and serve as the perfect selfie backdrop for attendees.

WhiteClouds produced this welcome display for the 2019 Consumer Electronics Show.

After formulating a plan that incorporated a 2D backdrop and a 3D display to accommodate the client’s budget, the Freeman and WhiteClouds teams set to work making 3D-ready files. WhiteClouds uses Autodesk Maya for prepress operations. The team elected to 3D print most of the figurines in the display – 11 pieces in total – with the exception of a game controller and the stage.

It was no easy feat; the final display spanned 18 x 6 ft. and required eight weeks of production. WhiteClouds used Creality 3D printers with PLA plastic, and a MultiCam 1000 CNC router. Most pieces were sanded, primed, bonded, sanded again and airbrushed with Createx paint.

As for the decision to print some pieces and cut others out of foam, Fowers said the game controller seemed like a simpler shape that would’ve been more expensive to 3D-print. But after finishing was more tedious than expected, the team wondered if 3D printing would’ve been the more efficient way to go. “The one thing about our industry is pretty much everything we do is a one-off,” Fowers said. “We take our past experience and try to make good decisions.”

ONE PROBLEM AT A TIME

Titanic Design (Mountain View, CA) is a large-scale 3D printing company established in 2016 when its founders saw a need for affordable 3D printing, particularly in the world of engineering. When I asked Tom Price, director of engineering and operations, what kind of clients a company like that serves, he said, “They have a problem that they need solved and they’ve heard 3D printing can help them.”

The problems Titanic has solved range from prototypes for groundbreaking sound-abatement technology to a 7.5-ft.-tall turbo fan engine to be used as a tradeshow prop. “3D printing is just another tool,” Price said. “The challenge is seeing where it works and where it doesn’t work.” He added that 3D printing, especially at this scale, is great for projects that are particularly unique, intricate or difficult to fabricate. Titanic commands a fleet of house-modified 3D Platform printers that can each churn out more than 35 cubic feet.

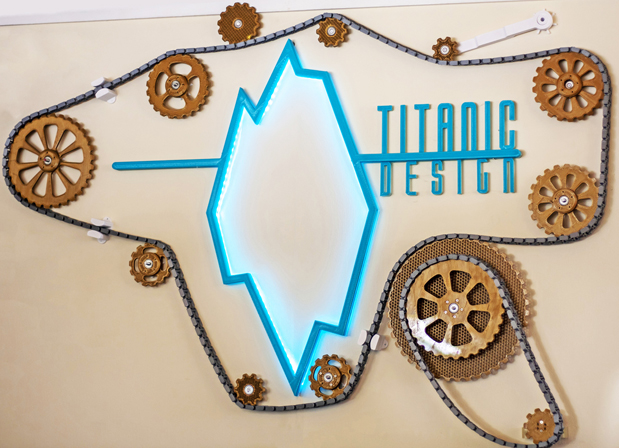

As for signage, the Titanic team decided to create a 3-ft., in-house display piece that would both test and show off their capabilities. “What would we be without a 3D-printed sign as a large-scale 3D printing company?” Price said.

The two-day job began with Titanic’s engineers adapting the company logo via Solidworks CAD software, but the plan wasn’t as simple as “print a logo and hang it up.” (It never is, is it?) The logo was engineered to print in two shell-like pieces in order to create a stand-out, backlit effect. The back piece is transparent and houses LEDs, and the front piece is teal. The sign looks as if it’s standing off the wall. Titanic used compostable, US-made bioplastic from Push Plastic.

Titanic Design created this in-house piece to display their 3D printing skills.

“I claim signage has some art to it,” Price said. Surrounding the logo element of the sign are functioning gears, which show off 3D printing capabilities, but are also a way for the Titanic team to test how well 3D-printed parts can hold up over time. The sign was hung in late 2018, and so far, so good.

What does 3D printing mean for the business of visual communication? Price reiterated his mantra that 3D printing is just “another tool in the toolbox. We by no means would say you should 3D print everything. You’re always going to have areas [in which] 3D printing can never compete – and I say that as a 3D printer,” he said. Titanic often collaborates with other fabricators, and Price added that traditional methods are still irreplaceable in many ways.